Psychedelics and the Art of Motorcycle Riding

“The real cycle you’re working on is a cycle called yourself.”

“Anxiety, the next gumption trap, is sort of the opposite of ego. You’re so sure you’ll do everything wrong you’re afraid to do anything at all.”

― Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

If you ride bicycles or motorcycles regularly this first part may be review. For the rest of you, in order to really talk about this topic I need to put it in the context of the mechanics of steering a bike.

It might seem obvious but two-wheeled vehicles do not handle like four-wheeled vehicles do. What’s not obvious is precisely how they differ. It also might surprise you that, at a very basic level, bicycles and motorcycles handle and steer the same way despite their size, mass, and speed differences.

Similarly to a planet that is in a constant state of falling when it orbits a star, a bike rider literally falls through a turn. No quotes, no italics, I’m not playing with words; you’re actually falling.

Mind blown? So was mine when I first learned about this.

I’ll do my best to summarise but please know that what follows is an extreme simplification of the elements and process of steering a bike at speed.

Steering a bike is, from a physics standpoint, incredibly more complex than steering an inherently stable vehicle such as a car with four wheels. There are several parts of a bike’s construction that make it handle the way it does. When you steer a car, the front wheels turn and the rigid frame follows: simple. A bike, however, has a frame that is not rigid. It flexes in between the wheels at the head tube on bicycles and steering head on motos.

The next point is that bike tyres have a rounded cross-section. Car tyres have a large flat surface that touches the road but a bike’s tyre curves to the sides allowing the bike to lean over with little resistance.

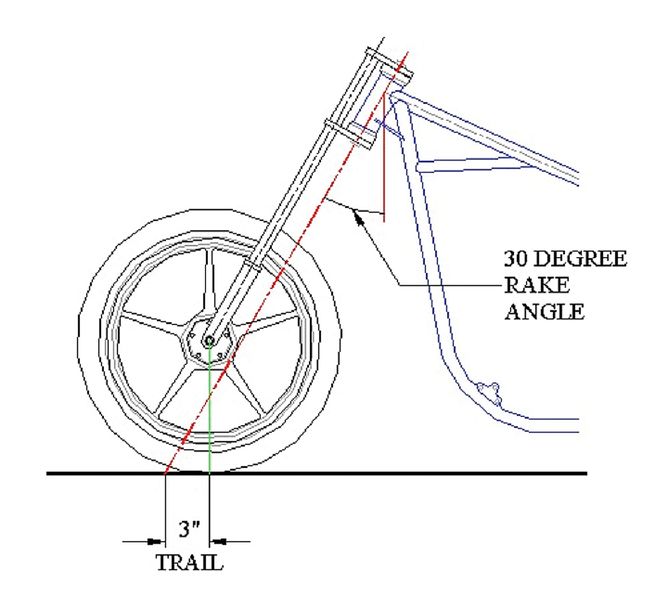

The third factor is that front wheels on bikes are raked. This means the wheel is mounted forward of the point where the front forks attach to the frame. The rake angle is determined by comparing the straight line running through the steering axis relative to true vertical.

Now visualise a bike from above moving down the road. Turn the bars, remembering that the part of the wheel touching the road will not deflect sideways but will keep rolling. By turning the wheel you flex the frame in the opposite direction (because of the rake) you’ve just pointed the wheel in. This flexion shifts the mass of the bike and rider and moves the centre of gravity to the side of the wheels. Also the wheel is now pointed slightly away from the direction of frame deflection adding to the shift in weight distribution. When the centre of gravity moves past the edges of the tyres’ contact patches you begin to fall to the side.

But don’t panic, you also have momentum in the direction you were traveling. As you fall and begin to turn your momentum is trying to push you back up and toward the outside of the arc. There is a sweet spot where your momentum balances out the pull of gravity that riders find instinctively; there is no time for calculations at 120kph. Our magical inner ear helps us figure out the complex calculus moment to moment. The bike and rider lean to the inside of the turn and you speed around the corner. This is why tyres are round, you’re now riding on the side of the tyre not the bottom. To go back in a straight line you steer into the turn and your momentum picks you back up.

Why this works is still not entirely clear to physicists; it’s that complex. There isn’t even full consensus on whether or not the front wheel, once fully in the turn, straightens parallel to the long axis of the bike or if you counter-steer through the entire turn.

Two notes on that, both anecdotal. First, if you look at the image of the racing bike, you may notice that the front wheel does appear to be pointing slightly ‘up’ or away from the turn a small amount. Second, I have consciously pushed the inside end of my bars the entire way through a turn. So take that for what it’s worth.

Though I fully admit I could easily be wrong my layman’s view is that I don’t notice the wheel returning to centre until I come out of the turn, I feel counter-steering through the entire arc.

It’s a fascinating point that all of this changes at slow speed, less than 12-15 miles per hour. The exact point of change depends on the geometry of each vehicle. Below this threshold, you steer into the turn like you would intuitively assume- turn the wheel to the left to go left.

All of these motions are extremely small and subtle and many riders do them without even noticing. I never heard about counter-steering until I had been racing bicycles for a couple years and a fellow cyclist told me about it. The next time I went for a ride I tested this idea. I pushed on the right side of the handlebars and by gum didn’t the bike lean and turn right? I had to do it about a dozen more times before I believed it.

So what does this have to do with psychedelics? The one thing I didn’t mention that is necessary to the turning process is the rider and his/her ability to control a speeding machine with the precise skill necessary to carve a turn in epic style. The more you lean the bike the more confidence you have to have in the machine, the physics, and in yourself…that last one is the rub.

A major symptom of the abuse I suffered was that I had very little self confidence. Though I would often wear a bravado-coloured mask at work and in public, inside I bubbling with self-doubt and fear. My father’s narcissism always put his own needs first, mine were never considered. I was trained to believe that I was incapable, inferior, and unworthy. I did not matter and I was never given the tools with which to navigate the world with any measure of self-assurance.

It is a fairly common symptom of child abuse that the child blames his or her self instead of the abuser. A child is programmed to instinctually trust and need a caregiver to help the child discover who they are. To a child, this need is so fundamental to their sense of stability that it can be effectively impossible for them to see the parent, the keystone of their universe, negatively. The child assumes the blame, internalises the abuse as being deserved, rather than remove the foundation of the family structure they are designed by nature to trust and rely on.

In my case this took a particularly destructive form. Because my father returned to my life just before I entered adolescence, the time of life when a boy naturally turns towards his male parent to learn how to become a man, I ended up rejecting my mother and putting my father in the position of the godhead. I would come to hate him but I would be an adult before I would finally have the strength to remove him from his throne. That adolescent need for a father, any father, anchored me to him in fundamental ways that reinforced my internalising of his abuse.

As an adult this manifested as complex behaviour and thought patterns perfectly explained by the late John Bradshaw:

“When healthy shame is internalized, it becomes toxic and destroys all balance and boundaries. You become grandiose: either the best, or the “best-worst.” With toxic shame, you are either more than human (superachieving) or less than human (underachieving). You are either extraordinary or you are a worm. It’s all or nothing. You either have total control (compulsivity), or you have no control (addiction).”1

My father demanded prescient perfection. If one did not anticipate his needs and fill them to his exact specifications, he became irate at best. I was called stupid, incompetent, lazy, fat, and a thousand other words that became a part of my own self-image but taken through the lens of his camera.

I therefore strove to be perfect in all things; when I wasn’t, I was an abject and useless failure. It is an impossible condition- needing to be better than everyone but believing you are worse than everyone. Even when I did something perfectly, or even extraordinarily, the worm-mind, what I now call the “inner critic,”2,3 was there telling me that I was unworthy, that I wasn’t good at all, that this was just a sham and a put-on.

That voice, a tiny demon on my shoulder with the face and voice of my father, flailed my soul with barbed whips nearly every moment of every day. It was a constant inner dialogue; you are ugly, you are disgusting, you are stupid and undeserving…more and worse, all day every day. The tiniest perceived error or misstep would unleash a torrent of vile, self-recriminating hatred and derision from the inner critic.

That I rode a motorcycle at all was a testament to the healing properties of time and distance; I had finally extricated myself from my father’s direct influence in an eruption of rage and grief at the age of 22. Over the years I had (very!) slowly started to heal a little merely because I had completely shut him out of my life and had not spoken to him since the day I screamed at him while he laughed mirthfully at my anguish.

I got my motorcycle endorsement at age 42 in the state of Oregon, on another coast and two decades after the last time I had been in his presence. Even though I had been an aggressive cyclist pushing the limits of what a road bicycle can do (I once hit 72mph going down a long hill in Morrisville, NY) motorcycles had intimidated me for much of my life; I didn’t think I was ‘man enough’ to ride.

To this day I’m not sure quite what prompted me to dive wholeheartedly into moto riding. I think there was some rebellion against the limitations my wounds had imposed as well as a desire to do something that scared me, to stretch my limits. A co-worker and friend who rode also had some influence, the stories he told about riding had the same theme- an adrenaline-filled good time.

I got my endorsement and soon the bike became my primary vehicle. I started small with the now commonplace first bike, a Ninja 250. I would eventually move quickly through larger sport bikes to aggressive street fighters like my Ducati Monster4 and eventually settled on big, heavy cruisers. I ride everywhere and in nearly every weather condition with the exception of when there is a possibility of ice or snow.

I logged thousands and then tens of thousands of miles relatively soon. I began the work of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy at exactly 44.5 years of age but still the sneering, snivelling voice of my father went with me every time I rolled out of the driveway.

I was a nervous rider desperately trying to seem confident. Because of the shame I felt for that anxiety I often rode more aggressively than I was comfortable with, forcing myself to ride like the seemingly fearless guys I saw every day. Slaloming through heavy highway traffic was a frequent, and at times extremely dangerous, pastime; I would whip the bike through tiny gaps between cars at a speed at which the tiniest mistake could have been fatal.

It was never enough, I could never do anything to prove I was worthy. The voice was still there- you suck, you’re a pussy, you don’t have the balls to be a real rider. His tone, his vocabulary, his voice.

It was especially noticeable when cornering. Cornering at speed, as I described, above requires confidence. The falling aspect was, for me, the biggest obstacle. You turn with your body by leaning into the curve, literally hanging yourself out to the side of the bike with unforgiving pavement screaming past right below. As I would approach a corner, every corner, his voice was there distracting and ridiculing me.

You’re going in too fast, your wheels won’t hold, you can’t do this, you’re too afraid.

As you can imagine, this all made cornering not only terrifying at times but far more dangerous than it should have been. Rule #1 of riding is to not get distracted and pay attention; when you get distracted and make a mistake is when you eat asphalt. His voice was a huge distraction and in my first year of riding I went tumbling down the road ass over teakettle a couple times because of the loss of focus. Thankfully those incidents were all at city speeds and not on the highway.

I would slow way down in corners, avoiding as much of the falling aspect as I could. I would unconsciously do what’s called counter-weighting- leaning the bike into the turn but moving my body to the outside, keeping my weight directly over the bike.5

Suffice it to say, I cornered like crap and I knew it. Every time I let off the throttle or hit the brake before entering a turn I cursed myself, hating my trepidation. I sometimes tried to force myself to do it the right way but it was often impossible to fight the deeply-held belief that I was simply incapable of cornering well.

And then something changed. That voice started to lose its power, it became quieter and moved farther away. As I progressed through my healing journey the old wounds finally began to scab over and my self-confidence, and self-esteem, began to grow. I realised that the voice was a fraud, it was the sham not me. My father did what he did because he was sick, a narcissist to the extreme, and the lingering taunts in my head came from that same wellspring of disease not from a source of truth.

Taking that agency away from him had unexpected benefits. I am happier and more content than I’ve ever been before, which was the goal if I could have ever said to have had one, but I’m also a better moto rider. That lack of confidence is gone, replaced with a wiser and kinder inner voice that sounds nothing at all like him. Now when I dive into a corner, feel the rubber grab the pavement and whip the bike around, and I’m hanging off the bike with my body stretched out into empty space that voice is cheering and just enjoying the hell out of the ride.

I can hang in the corners with other riders now. I’m not the most aggressive rider but I’m no longer the guy that is with the pack going into a curve and 100m off the back coming out of it.

I’ve also given up the stupid, showboat moves. No more whipping through traffic pell-mell at 80-90mph or more where the slightest unexpected move by a car could turn me into road pizza. No more going out to a deserted stretch of highway and having to pull myself forward on the bike because at 150mph the wind is doing its damnedest to blow me off the back. I’m content with my big, bulky couch on two wheels that I’ve never taken above 85, it’s too damned big to do half the stuff I used to anyway.

I never would have anticipated it but psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy literally made me a better motorcycle rider. More importantly, it made me a happier motorcycle rider. The inner peace that I feel today, the compassion that I am able for the first time in my adult life to feel toward myself, has changed the flavour and timbre of every moment.

I ride, I love it, and that’s enough for me these days. I ride how I want to ride and don’t worry about meeting some nebulous standard that no one cares about anyway. There are guys who corner far more aggressively than I do and I’m ok with that. Some corner much more slowly than I do and that’s ok as well. This isn’t a contest, it’s a way of life. Just get out there and ride.

And let’s be honest: if you ride a motorcycle you’re already a badass. You’re out there on two wheels, there’s nothing left to prove.

Notes and References

1 Bradshaw, J. (1988). Healing the Shame That Binds You. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications Inc.

2 Plotkin, B. (2013). Wild Mind. A Field Guide to the Human Psyche. Novato, CA: New World Library.

3 The ‘inner critic’ is one of the ‘loyal soldiers’ Mr Plotkin describes, fragmented aspects of the post-trauma personality that seek to protect us but can continue the trauma and abuse for years internally after the external abuse has stopped.

4 I really loved that bike. But its fast and nimble design encouraged me to do stupid things and really fed into my need to prove myself. I sold it to remove temptation. The kid who bought it did precisely what I was afraid of doing 6 months later; he cut a semi-blind corner too fast and hit an oncoming pickup truck head-on. The kid survived after a lengthy stay in hospital, the bike didn’t.

5 This technique is commonly used in off-road riding because of the very different traction conditions but doing it on the road was actually making a mishap more likely.